In our 2021 paper [1], David Kaftan, George Corliss, Ron Brown, and I explored how to generate enough extreme cold events to effectively estimate design day conditions. As we know, natural gas customers rely upon utilities to provide gas for heating in the coldest parts of winter. Heating capacity is expensive, so utilities and end users (represented by commissions) must agree on the coldest day on which a utility is expected to meet demand. In this blog, I discuss the problem of estimating the cold tail of the weather distribution, definitions of design day conditions, and methods for estimating these conditions.

As a motivation for accurate estimates of design day conditions, we need only recall the cold wave of early 2019 that broke temperature records across the American Midwest. This resulted in record-breaking natural gas demand [2] that put stress on the gas utilities infrastructure, i.e. their ability to provide enough gas to their customers during such extreme weather conditions. In the winter of 2021, some utilities in Texas were unable to provide enough gas during another cold event resulting in electric utilities losing their ability to run their natural gas fired plants [3]. Having the appropriate infrastructure requires accurate estimates of design day conditions.

The gas supply planning organization within a utility is responsible for ensuring that sufficient natural gas can be delivered to meet the customers’ demands, especially critical on extremely cold days when the customers’ needs are high. Utilities and regulatory commissions must agree on the weather characteristics of the design day – known as the design day conditions. Natural gas infrastructure is expensive, so determining the extremity of weather for which a utility must prepare requires balancing cost of the infrastructure and risk of demand exceeding capacity. Once a level of risk is agreed upon, utilities must determine the design day conditions that correspond to that risk.

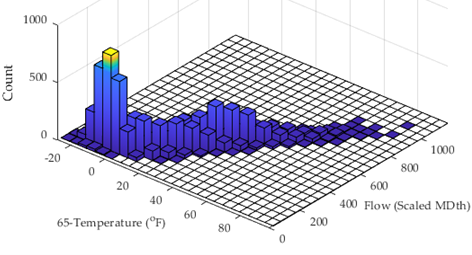

Determining the design day conditions is difficult because the likelihood of them occurring (i.e., once in 30 years) is very small compared to the amount of data available. This can be seen in Figure 1 where on the right-hand side (high demand and low temperatures) there are very few days.

Figure 1 – The number of occurrences at a given demand and temperature.

Design Day Conditions

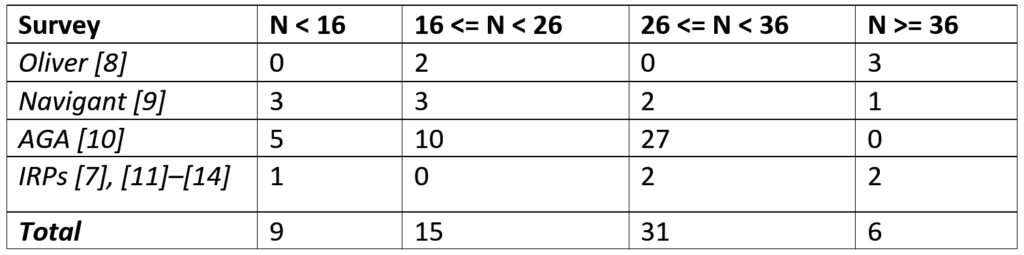

The characterization of design day conditions must be predictive of gas demand and understandable by a utility’s customer base. Temperature is such a characteristic with both predictive and understandable properties. The relationship between temperature and gas demand is well documented [4]–[6], and the public understands the utility’s commitment to heat their homes down to a certain temperature. The probability of design day conditions may be characterized as an event that has a 1/N probability of being below a given temperature (one or more times) in a given year [7]. Table 1 presents the 1-in-N year probability used by different utilities according to four surveys.

Table 1 – The 1-in-N year probability that defines an extreme event varies from utility to utility.

Estimating Design Day Conditions

The methods utilities use for determining design day conditions can be categorized into three approaches with increasing complexity: 1) choose the coldest day in last N years; 2) fit a distribution to historical temperature and calculate the temperature with the return period of N years; and 3) generate a large weather dataset, then repeat 2).

The first approach is to set the design day conditions as the coldest recorded day in the last N years [10], [12], [13]. Not only does this lack statistical rigor, but it also causes a serious logistical problem for utilities. When the coldest historic day falls out of the previous N years’ window, the design day conditions can change dramatically. Since these conditions are used for long-term planning, a large change in conditions from one year to the next can have serious consequences. Some utilities simply choose the coldest day on record [10], [11], [14]. This avoids the aforementioned logistic problem. However, the likelihood of such a day occurring is no longer linked to a likelihood factor – such as once in N years. Rather it is arbitrarily tied to the length of the weather dataset available.

The second approach fits a distribution to historical weather [7], [8], [11]. These methods can use the entire history of recorded weather to determine the design day conditions. However, the datasets that are used to fit these distributions are limited – the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has data back to only 1973 for many weather stations [15]. Therefore, the extreme quantiles – such as 1-in-30 years – are being estimated from relatively small datasets. The final approach is to use a weather simulator to create a large dataset of extreme events and fit a distribution to it.

Our Surrogate Weather Resampler (SWR) takes this third approach and is inspired by the question: what if an autumn cold snap occurred in the winter? To answer this question, the SWR removes the seasonality of autumn’s weather from the cold snap and applies the seasonality of winter weather. The SWR is split into two steps. First, a model is fit to temperature data with respect to season. Second, the residuals from the model are resampled. The resampled residuals are input into a temperature model to generate surrogate temperatures. For a detailed description of the SWR please read our paper [1].

References

[1] D. Kaftan, G. F. Corliss, R. J. Povinelli, and R. H. Brown, “A Surrogate Weather Generator for Estimating Natural Gas Design Day Conditions,” Energies , vol. 14, no. 21. 2021.

[2] A. Lee, “Extreme cold in the midwest led to high power demand and record natural gas demand,” Today in Energy – U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=38472. [Accessed: 11-Aug-2021]

[3] “Regulators knew of freeze risk to Texas’ natural gas system. It still crippled power generation.” [Online]. Available: https://www.houstonchronicle.com/business/energy/article/freeze-risk-texas-natural-gas-supply-system-power-16020457.php. [Accessed: 21-Sep-2021]

[4] H. Sarak and A. Satman, “The degree-day method to estimate the residential heating natural gas consumption in Turkey: A case study,” Energy, vol. 28, no. 9, pp. 929–939, 2003, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0360-5442(03)00035-5.

[5] H. Aras and N. Aras, “Forecasting residential natural gas demand,” Energy Sources, vol. 26, no. 5, pp. 463–472, 2004, doi: 10.1080/00908310490429740.

[6] S. R. Vitullo, R. H. Brown, G. F. Corliss, and B. M. Marx, “Mathematical models for natural gas forecasting,” Can. Appl. Math. Quaterly, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 807–827, 2009.

[7] Columbia Gas of Pennsylvania, “2015 Summary report,” Canonsburg, PA, 2015.

[8] R. Oliver, A. Duffy, B. Enright, and R. O’Connor, “Forecasting peak-day consumption for year-ahead management of natural gas networks,” Util. Policy, vol. 44, pp. 1–11, 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.jup.2016.10.006.

[9] Navigant Consulting, “Analysis of peak gasday design criteria,” Toronto, Ontario, 2011.

[10] American Gas Association, “Winter heating season energy analysis,” Wasington, D.C., 2014.

[11] Intermountain Gas Company, “Integrated resource plan 2019-2023,” Boise, ID, 2019.

[12] Cascade Natural Gas Corporation, “2016 Integrated resource plan,” Kennewick, WA, 2017.

[13] Vermont Gas Systems, “Integrated resource plan 2017,” South Burlington, VT, 2017.

[14] Avista, “2018 Natural gas integrated resource plan,” Spokane, WA, 2018.

[15] A. Smith, N. Lott, and R. Vose, “The integrated surface database: Recent developments and partnerships,” Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc., vol. 92, no. 6, pp. 704–708, 2011, doi: 10.1175/2011BAMS3015.1.